Cite this paper:

Lelièvre E., « OFabulis and Versailles 1685: a comparative study of the creation process behind video games on historical monuments », in Proceedings of Playing with History 2016, DiGRA/FDG Workshop on Playing with history: Games, antiquity and history, Digra digital library, 2016, 11 pages.

Abstract

This paper explores the specificities of the creation process behind video games focusing on historical monument through the comparison between two point-and-clicks: OFabulis and Versailles 1685. The study is based on the authors’ interviews, log books and work documents. The comparison seems to reveal that three elements are inherent to this type of video games: participation of cultural institutions in the game design right from the start, leading scenario with compromises between history and fiction, ad hoc multimedia systems with limited gameplay and realistic rendering.

Keywords

Video game, cultural heritage, history, point-and-click, comparison

Introduction

Experimental video game OFabulis, a project directed by the author of this article, was inspired by video game Versailles 1685, which is 18 years older. Both games focus on monuments, history and heritage. However, apart from their topic, these two projects do not seem to have much in common: the context in which they were created, their gameplay, their scenario and graphic identity are different.

Through interviews with the designers of Versailles 1685, we have yet managed to find numerous similarities in their creation process: against all odds, these two projects seem to share many elements in common.

One may wonder whether there is a specific creation process when it comes to video games promoting historical monuments. In this article, we will try to show these specificities by comparing Versailles 1685 and OFabulis.

We hope that a better understanding of the processes behind the creation of this kind of video games facilitates their analysis by researchers. It should be noted that video games promoting historical monuments seem to be the focus of much attention lately, as shown by the release in 2015 of the games Mystères ma ville Limoges (Dreamagine studio, 2015) and Le Roi et la Salamandre (Pinpin Team, 2015). This article also aims to raise awareness of the video games industry with regards to the opportunities and constraints inherent to the creation work in partnership with cultural institutions.

To conduct this study, we have mostly resorted to a methodology called research-creation, taken from the field of arts (Gosselin, Le Coguiec, 2006). It consists in studying the process of creation of a work from within, based on the authors’ log books and work documents. The study is conducted by the designer of the artistic work themselves, as is the case here with OFabulis, in which the designer of the game conducts the research. When the creation process is studied by someone who has not taken part in the creation of a work, one talks about poïesis (Passeron, 1996), in which case the analysis is based on interviews with the game designers and the study of work documents. This is the case of Versailles 1685.

We will first describe these video games, before we analyze the essential aspects of their creation process: origin of the projects, design of the technical devices and negotiation of the place of fiction in the scenario.

Presentations of Versailles 1685 and OFabulis

Versailles 1685

Versailles was released in 1996 under the full name: Versailles 1685: a Game of Intrigue[i]. It is an investigation game. Its gameplay[ii] falls within the “point-and-click”[iii] category. The game world is a historical reconstitution of 1685 Versailles, at the pinnacle of Louis XIV’s glorious reign. The game content is historically accurate and its design was technically very innovative at the time (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Screenshot from the game Versailles 1685

The player embodies Lalande, a fictional “blue guard” of the Palace of Versailles. He has to solve a case in one day, in order to prevent a madman from setting the palace on fire. Throughout the investigation, the player will wander the palace and gardens and live like a member of the Court.

Versailles 1685 is a first-person game. The player never sees the character they are playing. Once inside a room, the player cannot make any other move but rotate the camera around them. They can examine and interact with objects, talk with non-playable characters (mostly historical figures), or change rooms.

Versailles 1685 was co-produced by the Réunion des Musées Nationaux (RMN), Canal+ Multimédia and Cryo Interactive. It was designed by Cryo Interactive, the Éditions Textuel and Béatrix Saule from the Palace of Versailles.

The game was produced by quite a significant team for the time. The game credits include 74 people – 47 for Cryo alone – without taking the voice actors into account.

The game budget was significant too, since it eventually cost 2.3 million Francs[iv]. The game was a big hit: according to the game producer, over 2 million units were sold across 14 countries[v].

OFabulis

OFabulis is a free experimental game released on the Internet in June 2014 and available up until June 2015[vi]. It is an investigation game, the gameplay of which is a mix between “point-and-click” and MMORPG[vii]. OFabulis takes place in nineteen monuments registered at the Centre des Monuments Nationaux (the Mont-Saint-Michel abbey, Pantheon, Villa Savoye, megalithic complex of Carnac, etc.). The game world is both contemporary and fantastic. The investigations that the player will carry out deal with history, architecture and legends surrounding the monuments.

The player creates a character. They choose its gender, facial features, hair and class. Being a multiplayer game, players can meet in the monuments of OFabulis via their avatars. They can also choose to make groups so as to play together more regularly.

Figure 2: Screenshot from the game OFabulis, exploration of the Saint-Denis Basilica

OFabulis starts in the Saint-Denis Basilica, with the discovery of a notebook belonging to a certain Pierre Roux, whom the players must find (Figure 2). The notebook includes riddles that must be solved in order to pass legendary doors. These doors lead either to other monuments in the game, or to an imaginary version of these monuments where the players can meet historical (Voltaire, Mazarin, Aregund, Saint Louis) and mythical characters (Melusine, Cybele).

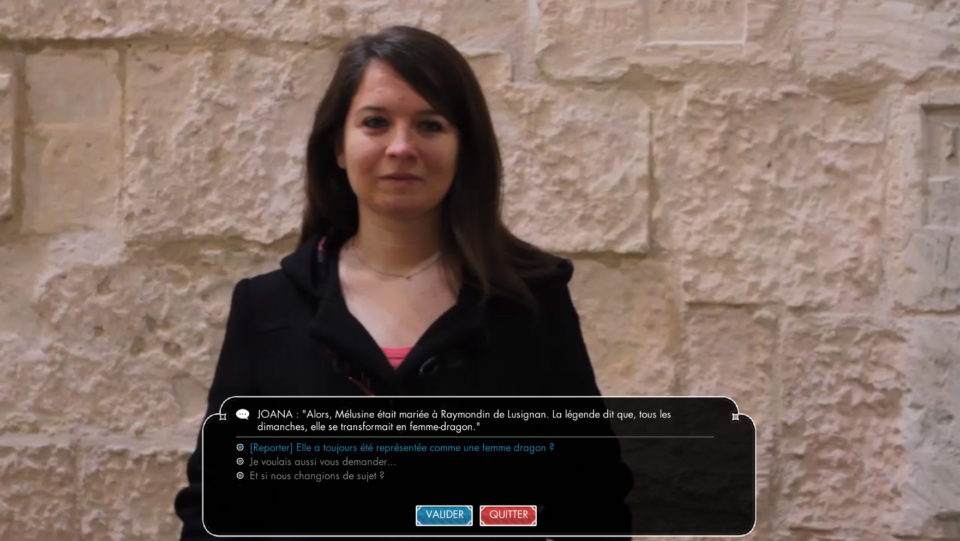

In the real world of monuments, players are to meet real agents, recreated in 3D and filmed for the occasion (Figure 3). The dialogues allow the player to learn about the history of the monuments and the agents’ trade.

Figure 3: Screenshot from the game OFabulis, interactive video with agent Joana

Technically speaking, graphics in OFabulis are a mix between photographs, 3D and video. Players are represented by 3D avatars, in third-person view, which can be moved by clicking on the ground, which leads to new hints or dialogues. However, they cannot change the camera angle. The player uses the mouse to move, click on hints and talk with the agents via interactive videos. The keyboard can also be used to interact with other players and write the keywords for the legendary doors.

The game has gathered over 2,000 subscribers over the servers opening period.

Conclusion of the presentations

At first sight, Versailles 1685 and OFabulis seem to have the same gameplay: an investigation game, mostly mouse-controlled. The differences between the two games are yet significant. For example, in Versailles, players are free to look around them, while the camera is static in OFabulis. However, the latter allows for player movement in the stages and offers a multiplayer mode.

Graphically speaking, the two games are very different. Versailles includes 3D scenery, while the historical monuments of OFabulis are made up of photographs from actual monuments mixed with 3D characters, videos and real-time special effects.

The scenarios of the two games differ greatly too, just like the context of their creation. Cryo was indeed a major studio at the cutting edge of technology at the time Versailles was released. On the contrary, OFabulis was created by a small team consisting mostly of academics and employees of Emissive.

Let us now describe the common points revealed by our comparison of these two games’ creation process.

Creation process of Versailles 1685 and OFabulis

Origin of the projects

Behind project Versailles 1685, one finds the association of the Réunion des Musées Nationaux (RMN) and Canal+ Multimédia in order to release a CD-Rom presenting the Palace of Versailles. The RMN is a public body in charge of the management of the greatest French museums (Louvre Museum, Grand Palais, etc.). It also used to manage the Palace of Versailles at the time. Canal+ is a major player of the French television industry.

The Éditions Textuel were approached right from the beginning. They were asked to participate in the project, namely by backing the documentary dimension of the CD-Rom with historical and iconographic content. An invitation for tenders was organized for the technical production. It was won by Cryo Interactive, a French video game studio which was quite successful at the time (Ichbiah, 1997), with a few big hits such as Dune (Cryo 1992). Their project reached far beyond the initially planned documentary CD-Rom, since they proposed what was then regarded as an unexpected and ambitious “cultural game”.

“Gedeon was very tame. It was very tame because they didn’t dare to take risks, everything was made of drawings and then simply splashes of colors (…) And then there was Cryo, which went right ahead. We were a bit scared by Cryo at first, so we decided to vote. (…) Canal+ and I said that, since we needed a game, we might as well straight out go for a game” Interview with Béatrix Saule, custodian of the Palace of Versailles, about the selection of Cryo for the production of the CD-Rom on Versailles, 3 September 2015.

OFabulis was designed in 2013. Patrick Monod from the National Monuments Centre was commissioned to prepare the 100th birthday of the institution in 2014. He wanted one of the centenary events to target young adults, so that he got in touch with the author of this article, a teacher-researcher at the Centre d’Histoire Culturelle des Sociétés Contemporaines (Centre for the Cultural History of Contemporary Societies) of the University of Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines. Since Monod had no preconceived idea, the author quickly proposed a multiplayer point-and-click video game set in monuments, where players would meet the agents and legendary characters. Emissive agreed to produce the game. Funding was quickly obtained from the Île-de-France Region to produce the prototype. The alpha version of the game was released in June 2014.

These video games were designed at the initiative of cultural institutions, although OFabulis was supported by a research laboratory, the CHCSC. This is an important fact, for cultural institutions do not have the same objectives as video games producers, or researchers. The project must promote monuments without compromising the scientific rigor and historical authenticity which the institution is responsible for. Therefore, these projects are distinct from other video games designed by video games publishers, even when the latter have called on historians like Jean-Clément Martin, an expert in the French Revolution, who has worked as a consultant on Assassin’s Creed Unity (Ubisoft, 2014) (Fagon, 2015).

Design of the technical systems

Since both games focus on monuments, the way the latter are presented was a major issue during the creation process of these projects.

In the case of Versailles 1685, the objective consisted in creating a version of the Palace of Versailles as it was in 1685 with 3D computer graphics. The Palace of Versailles management wanted outstanding scientific quality, a representation of numerous palace areas and gardens, and top-notch rendering, to match the prestige of the place. Although part of the graphic design work could resort to photographs of today’s palace, historical engravings and notes were also used to recreate part of the scenery, because of the numerous changes the palace had undergone. Besides the difficulty in achieving a high-quality 3D reconstitution, the main concern was to make the game available to the majority of players, despite the technical limitations of the computers of that era. Consequently, a real-time 3D presentation was out of the question. A new and adequate system had to be found.

As for OFabulis, historical re-enactement was not the focus of attention, since the objective was to represent the monuments as they are nowadays. However, the challenge consisted in bringing out their beauty in a budget multiplayer game. It was all the harder than 19 monuments had to be recreated, some of which were as big as the Palace of Versailles.

Both projects have adopted similar strategies to take up these challenges at the crossroads between game design, graphic design and computer development.

The first strategy consisted in implementing a specific technical system that would break away from the models of that era. A balance had to be struck between the need for an authentic scenery, interaction opportunities and technical limitations, which could not be achieved through traditional techniques. Versailles managed to do so by using “Omni 3D”, while OFabulis relied on “mixed spaces”. In both cases, these projects were pioneers in these technologies.

Omni 3D in Versailles allowed players to look around them: a spherical image was calculated around every possible point of view. Cryo had been working on this innovation before project Versailles 1685. However, this feature was fully realized in this game, which also was its first implementation:

“I had told them ‘It is not worth it if you cannot look around you and see the ceiling in the Grands Appartements of Versailles.’ At the time, I did not know that they were developing Omni 3D. So, there was this convergence of possibilities, that of a first-person view and that of being able to look all around oneself, which definitely helped. There was also a great technical progress.” Interview with Béatrix Saule

In OFabulis, the challenge did not only consist in creating high-quality reconstructions of numerous existing monuments, but also in allowing a great number of players to interact within this scenery, including with filmed non-playable characters, while keeping the game light enough to have it run smoothly on tablets. The chosen solution, called “mixed spaces”, is a mix of photographs, real-time 3D and video.

The second strategy consisted in selecting parts of the monuments only, rather than showing them entirely, as explained by Sophie Revillard, game designer of Versailles, in her end-of-course thesis:

“Considering that it was impossible to model the palace or gardens in their entirety (…), our work consisted in choosing the areas to model. The criteria were the following: their historical importance and CGI feasibility. Obviously, a CD-Rom about Versailles could not but include the Hall of mirrors. On the contrary, the Cabinet du Conseil, which in 1685 had its four walls covered in mirrors, was too difficult to model because of the reflections that were supposed to be endlessly repeated.” (Revillard, 2005)

In OFabulis, the criteria for the selection of the spaces in the monuments were different. The mixed spaces system required an elevated camera angle, so that high-angle shots could be taken with a wide enough view as to see all avatars at once, which was not possible in every area. Besides, we had to offer some kind of logical connection between the spaces, with visible exits, as seen in the “simple actions” figure (Figure 4). Depending on the monuments, 4 to 11 spaces were selected.

Figure 4: Image showing the « Players’ simple actions in the game areas” (Lelievre, 2014)

The selection of spaces was facilitated by the fact that players cannot move completely at will inside the monuments of Versailles 1685 and OFabulis.

Negotiation of the place of fiction in the scenario

As in most point-and-click games, the game mechanisms of Versailles 1685 and OFabulis are quite simple. However, the role of the scenario is crucial, with an extensive textual content.

The scenario of these two games stands at the crossroads between history and fiction, but their approaches are different.

The scenario of Versailles 1685 is linear and has players solve a plot by following Louis XIV over the course of a day. Although fictional, the plot is plausible. It is as much rooted in the reality of the era and historical characters as possible. It is based on Béatrix Saule’s work on Louis XIV’s court, with a focus on the King’s everyday life at Versailles. At the time, Mrs. Saule was one of the custodians of the Palace of Versailles. The draft of the scenario was written by Philippe Marie and the Éditions Textuel, but it failed to meet Béatrix Saule’s need for historical requirement.

“There was this first draft: The King wakes up, the cock crows. Saint Simon and Molière were there. Molière died in 73, while Saint Simon was born in 75. Everything was amended, so I told them, listen, we cannot approve that.” Interview with Béatrix Saule

Consequently, she rewrote the scenario with Sophie Revillard. Béatrix Saule focused on the background, while Sophie Revillard wrote the plot and most riddles. The goal was to immerse the player in the court of Louis XIV in 1685 and be as true as possible in terms of our historical knowledge of the atmosphere, palace and characters of this era.

“Versailles was like being plunged in a society with its specific laws. Therefore, the player would have to understand what was mandatory and what was prohibited in the Court. This is similar to an anthropological approach.” Interview with Béatrix Saule

In OFabulis, a trick of the scenario was implemented in order to give fiction more freedom: the game takes place in two very distinct spaces: the real world and that of legends. These legendary worlds are not historical, but imaginary. They interweave both the past and present of these monuments and the legends about them:

“The existence of legends induced the creation of parallel worlds. These worlds reflect our reality and are yet inhabited by legendary characters. Most legendary worlds have been built around myths involving these characters.

Some of these legendary worlds are close to reality. These are the worlds the legends of which are the most well-known or closer to the truth. One can partly identify the places that inspired these legends, but these worlds seem shallow, inconsistent.

On the other hand, other legendary worlds are so remote and forgotten that they are drifting, deprived of anchor. It is very hard to find any reference point and of course, to find how to access it. Whenever the real world shows through, it seems distorted and abnormal.” (Lelièvre, 2013b)

The legendary worlds would distinguish themselves from the real world through a visual effect and specific music (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Screenshot from the game OFabulis, legendary world of the Mont-Saint-Michel

Questioned about their experience of the game, players seem to have enjoyed and understood the use of these legendary worlds:

“In fact, I found it interesting to see a real difference between the reality of the place and the legendary worlds, materialized by this change in the image’s texture. There is a genuine difference and one can see the shift from reality, historical reality, to something else. The separation between the documentary and pure history is very clear too.” Interview with clara57 conducted after the questionnaire, 27 August 2015.

The historical content of the game was indirectly brought through the riddles, exploration of the monuments and dialogues with non-playable characters (agents and legendary characters). To create this content, the OFabulis team used “feeding” documents produced by the personnel of the monuments. These documents answered the following questions:

“Who are the main characters of these monuments (historical and legendary)?

What are the main myths and legends surrounding this monument?

What myths and legends surrounding this monument are little known?

What uncanny/funny/extraordinary events really took place in this monument?

Do you have any story on the trade of agent?

Has any strange person ever visited the monument? What happened?” (Lelievre, 2013a)

Both games show the former need for profuse and reasoned documentation, which is necessarily produced by heritage experts. Without this preparatory work, the content and riddles of the game would not be historically satisfactory, both quantitatively and qualitatively. However, offering more than a virtual tour requires game mechanisms that only game designers can create. Therefore, this kind of project seems to demand a partnership between heritage specialists and video game professionals.

As it happened, this was way more problematic in the case of Versailles 1685 than OFabulis. In 1995, the world of video games was still nascent, almost unknown to cultural institutions and the Cryo teams had never had the opportunity to work with these institutions. The misunderstandings between the different designers of Versailles lead to significant tensions:

“As we settled for an adventure game, we had to have a plot. We had to develop a suitable environment (…) This is where we found ourselves kind of stuck, because there would always be something impossible. What’s-his-name cannot have said this, what’s-her-name cannot have done that, this character could not have existed. (…) They were the keepers of Versailles. We just couldn’t tarnish the image of Versailles and had to be very cautious with its representation. They were very concerned about what we were going to do.” Emmanuel Forsans

One of the main challenges of this kind of project consists in striking a compromise between these two categories of experts, whose cultures are sometimes different.

Conclusion

The comparison between Versailles 1685 and OFabulis seems to reveal that certain elements are inherent to the type of video games promoting historical monuments:

- cultural institutions participate in the game design right from the start,

- the scenario is leading, but the negotiation between fiction and history requires compromises,

- the multimedia systems are adapted to graphics promoting the monuments, the rendering is realistic, but the gameplay is limited.

Of course, the comparison between only two games is not enough to deduce systematic rules of design for games dealing with cultural heritage. The specific elements that have been brought out in this article must be confirmed by studies on the creation process behind numerous projects of this kind. However, we do hope that it will provide useful information to the future studies on this topic.

Endnotes

[i] French title: Versailles 1685 : Complot à la Cour du Roi Soleil

[ii] The term gameplay associates the “game”, which is similar to the “ludus” described by Roger Caillois (Caillois, 1992) and “play”, a game without rules that is closer to the “paida” defined by Caillois. This association highlights the tension between the game rules and the player’s appropriation of these during a game. In this sense, the term gameplay describes the experience resulting from the negotiation between the game rules and the player’s behavior. By extension, this term is used by game designers to define the expected user experience. According to Jesper Juul, gameplay is the definition of rules and players’ interaction opportunities (Juul, 2005).

[iii] Point-and-click gameplay refers to games in which interactions are mainly triggered by mouse-clicks. Usually, these games are graphic adventure games, like Myst (Brøderbund Software, 1993).

[iv] Which amounts to €438,000, without taking the cost of living evolution into account.

[v] This data was provided from memory by Emmanuel Forsans, producer of Versailles 1685 and member of Cryo, on 22 July 2015. We have been unable to collect verified or more accurate data on the game sales yet.

[vi] The alpha version of the game was released as part of the Futur en Seine 2014 festival. The official experimental version was released in September 2014.

[vii] MMORPG: Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Game. These games, the most famous of which is World of Warcraft, take place in persistent worlds where a great number of players meet through a chosen and upgradeable avatar.

Bibliography

Caillois, R. Les Jeux et Les Hommes. Gallimard, Paris, 1992.

Cryo Interactive, Canal + Multimedia, Éditions Textuel (1996) Versailles 1685 : Complot à la cour du Roi Soleil. Cryo Interactive, Canal + Multimedia et la Réunion des musées nationaux.

Cryo Interactive (1992) Dune. Virgin Interactive.

Dreamagine Studio (2015) Mystères ma ville Limoges. Dreamagine Studio.

Fagon, L. “Saisir L’histoire Par Les Jeux Vidéo, Compte-Rendu de La Séance Du 30 Novembre 2015 Autour de Jean-Clément Martin.” Re/lire Les Sciences Sociales, December 3, 2015. Available at http://relire.hypotheses.org/429.

Gosselin, P., Le Coguiec E. (eds). La Recherche Création : Pour Une Compréhension de La Recherche En Pratique Artistique. Presses de l’Université du Québec, 2006.

Ichbiah, D. Bâtisseurs de rêves: enquête sur le nouvel Eldorado des jeux vidéo. F1rst, Paris, 1997.

Juul, J. “Half-Real: A Dictionary of Video Game Theory.” Half-Real: A Dictionary of Video Game Theory, 2005. Available at http://www.half-real.net/dictionary/.

Lelièvre, E.. “Demande de Participation Au Projet Ostia Fabulis,” August 6, 2013.

———. “Game Design Document : Ostia Fabulis,” 2014.

———. “Ostia Fabulis – Scénario Global,” 2013.

Lelievre E. (2014), OFabulis. Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, Centre des Monuments Nationaux, Emissive.

Passeron R., La naissance d’Icare: éléments de poïétique générale. Ae2cq éd, Paris, 1996.

Pinpin Team (2015) Le Roi et la Salamandre. Centre des Monuments Nationaux.

Revillard, S. “Vers Un Jeu Culturel.” End-of-course thesis, Mastère Multimédia-Hypermédia ENSBA/ENST, 2005.

Ubisoft Montréal (2014), Assassin’s Creed Unity. Ubisoft.

Access this paper on DIGRA digital library : http://www.digra.org/digital-library/publications/ofabulis-and-versailles-1685-a-comparative-study-of-the-creation-process-behind-video-games-on-historical-monuments/

Proceedings of Playing with History 2016

DiGRA/FDG Workshop on Playing with history: Games, antiquity and history

© 2016 Authors & Digital Games Research Association DiGRA. Personal and educational classroom use of this paper is allowed, commercial use requires specific permission from the author.